From the January 29, 1988 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

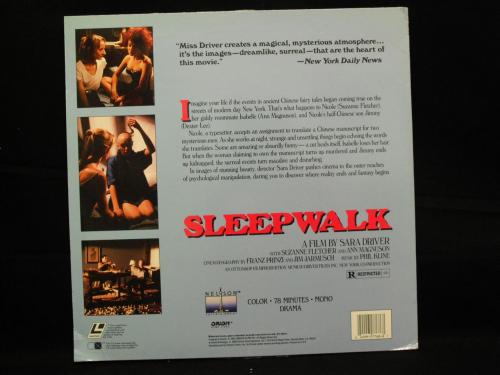

SLEEPWALK

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Sara Driver

Written by Driver and Lorenzo Mans

With Suzanne Fletcher, Ann Magnuson, Dexter Lee, Steven Chen, Tony Todd, Richard Boes, and Ako.

The French term fantastique — which emcompasses science fiction, comic strips, Surrealism, sword and sorcery tales, and many other forms of fantasy — suggests an attitude toward the imagination that is distinctly different from the Anglo-American model. In our more empirical culture, reams of verbiage are devoted to distinguishing science fiction from fantasy, and legislating certain laws of etiquette to govern both — rules of internal consistency and narrative coherence decreeing that all breaches with recognizable reality stem from the same premises, whether these premises be scientific, purely fanciful, or some mixture of the two.

The French tend to be freer and looser about such matters, which helps to explain why such films as Les visiteurs du soir, Picnic on the Grass, Last Year at Marienbad, Je t’aime, je t’aime, Alphaville, Fahrenheit 451, Celine and Julie Go Boating, and Deathwatch pose to English and American temperaments certain problems that are not posed by The Wizard of Oz, Things to Come, It’s a Wonderful Life, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Exorcist, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Blade Runner. The most common objection to the French examples might be, paradoxically, that they’re not “real” enough as stories — that the free-form quality of their inventions impedes the “natural” story-telling flow that we associate with the American examples.

All this might at first seem irrelevant to a discussion of Sleepwalk, an American independent feature set in lower Manhattan — and one, incidentally, whose least sympathetic character is a young Frenchwoman. But Sara Driver’s film won the prestigious Georges Sadoul Prize in France and enjoyed a respectable run in Paris, while it has garnered a much cooler reception in the United States — which may explain why it is arriving in Chicago 20 months after its premiere, in the Critics’ Week, at the 1986 Cannes Festival. And certainly the film’s free-floating fantasy and the blatant transparency of its narrative — its capacity to be seen for the artifice that it is — are a lot closer to fantastique than they are to the more logically circumscribed forms of fancy celebrated in this country.

In its initial stages, at least, the film’s plot seems to promise the kind of gradual revelations and explanations that we expect from a mystery thriller. A Japanese woman (Ako) places an ancient Chinese manuscript in a cabinet and leaves the room; seconds later, a black man (Tony Todd) enters, moving stealthily and like a dancer, and makes off with a portion of it, only to be chided by his Chinese master (Steven Chen) on the street for not procuring the first page. In a nearby copy shop on the Lower East Side — all of the film’s action is confined to a few city blocks — the heroine, Nikki (Suzanne Fletcher), who works at a computer terminal, is visited first by her vain and petulant French roommate, Isabelle (Ann Magnuson), who has just purchased some red shoes and wants to borrow money, and then by the two manuscript thieves, Dr. Gou and Barrington Rutley III.

It emerges that Nikki speaks Chinese — she notes that “gou” is the Chinese word for “dog,” and relates this to the Year of the Dog — and the duo hire her to translate and transcribe the Chinese manuscript, cautioning her not to let it out of her sight. After working late at the copy shop on the translation, Nikki walks home, encountering two strange children, separately, and an executive who turns and barks at her on the street. She fixes dinner for herself and her Chinese son Jimmy (Dexter Lee), and learns about a couple of phone messages left with Jimmy and Isabelle by her boyfriend, Jack. She phones Jack but there’s no answer.

The next day the Japanese woman, who calls herself Ecco Ecco, appears at the copy shop, wants to know where Nikki got the Chinese manuscript, and after leaving a deposit to assure Nikki’s suspicious boss that she needs some work done, makes an appointment with Nikki on a rooftop a few blocks away. Nikki goes to meet the Japanese woman, but she doesn’t appear; shortly afterward Nikki learns that she’s been found dead, strangled by her own hair, with three of her fingers cut off. Before long, while working on the manuscript, which smells increasingly like almonds, Nikki starts to hear Ecco Ecco’s disembodied voice. Various events alluded to in the manuscript happen to Nikki and the people around her: a wound on her finger magically heals, and Isabelle suddenly loses all of her hair. Spontaneously, Nikki proposes that Isabelle drive to Atlantic City and wait for her hair to grow back, taking Jimmy along; she gives Isabelle $300 and wakes Jimmy up — it’s the middle of the night — so they can leave immediately in Nikki’s car.

Rather than recount the remainder of this blatantly outlandish plot — which includes the inadvertent kidnapping of Jimmy by a car thief in Chinatown — I should stress that long before we reach this point, it has become apparent that Driver does not intend to resolve any of the mysteries she sets up, or even establish a ground base of reality that would allow us to situate ourselves comfortably in relation to the fantastical events. It is true that certain occurrences relate to one another thematically — a mysterious black dog, which guards and roams the streets, seems to bear some relation to the Year of the Dog, Dr. Gou’s name, and the barking executive; and Barrington progressively loses more and more of his fingers, which can be related to the injury and recovery of Nikki’s finger and the mutilation of Ecco Ecco’s corpse. But these clusters of motifs remain as opaque as the various twists of the plot remain transparent.

The resemblance of the plot of Sleepwalk to automatic writing — the uninhibited stream-of-consciousness exercises practiced by the Surrealists — extends even to certain ruptures in style. When we’re first introduced to the copy shop and the various workers there, Driver presents each of them in turn performing a rhythmically monotonous task — collating pages, tearing off strips of paper, examining slides, and so on — with a witty sense of rhythm and cadence suggesting Jacques Tati. Much later in the film, this pattern is developed further when Nikki is all alone in the shop at night: the various machines turn themselves on and assume a life of their own while all of the phones start to ring in their separate tonalities, creating a similar musique concrète. Yet most of the other scenes in this setting are more naturalistic. The overall impression is a feeling of instability in style as well as plot — a disequilibrium often experienced in the styles of acting as well. (Barrington, for instance, is presented in turn as a graceful dancer, a former academic, an allegorical representation of fate, and a film noir thug.) Isabelle losing all her hair is odd enough to begin with, but Nikki suddenly deciding to pack her and Jimmy off to Atlantic City in the middle of the night is even odder, and odd in a different way — like one dream modulating unexpectedly into another.

Driver’s one previous film, You Are Not I (1982) — a 50-minute, black-and-white, 16-millimeter adaptation of a Paul Bowles story about a schizophrenic, also starring Suzanne Fletcher — was also witty as well as unsettling, but there the sense of hallucination was rigorously controlled by the drift and shape of the story. Here the story seems to function mainly as a pretext for generating moods, images, and characters, rather than the other way around; and spectators who try to grab ahold of it will find it crumbling to dust between their fingers, in the same way that the ancient Chinese manuscript eventually self-destructs. (Driver has noted that the story told in this manuscript — which we periodically hear being recited by Ecco Ecco offscreen and by Nikki at her terminal — was composed by combining four separate fairy tales: one Chinese, one African, one from the Brothers Grimm, and a fourth that she made up herself.)

Working, in other words, without a net — and, indeed, with a tightrope that only functions as long as we don’t look at it too closely — Driver invites us to enter her nocturnal fun house, and to close the door firmly behind us. For spectators willing to accept her dare, the movie offers a singular array of thrills and enchantments. Both its images and sounds are ravishing — it’s hard to think of a better looking and sounding American 35-millimeter film made in 1986 — and immensely seductive if one is able to accept them as part of shifting moods and poetic reveries rather than as functional building blocks in a logically constructed house of fiction.

It makes more sense to locate the meaning of Sleepwalk in a few striking images and scenes than to attempt to rationalize the rambling plot into a separate meaning of its own. Each of the examples given below is a crystallization that poetically illuminates the film as a whole; none of them begins to “explain” the plot, but each goes a long way toward justifying it:

1. Take the matter of Nikki’s unseen boyfriend, Jack — apparently out of town during most of the film’s events, he is a character who never puts in an appearance. When Nikki tries to return his calls, Driver cuts to the phone ringing in his empty bedroom — a small, Magritte-like chamber containing an unmade bed, the brightly lit white phone, an open window, and a full-size double bass poised upright inside its case. That’s all that we ever learn about Jack, but the enigmatic image has a haunting clarity and beauty — an unattached, signifying presence — that stays in the mind.

2. Close-ups of the Chinese manuscript and extreme long shots of the Manhattan skyline at night recur frequently, punctuating the action. After a while, these two emblems begin to function interchangeably, suggesting a notion of the city as indecipherable text, a cluster of unreadable characters (in both senses of the word). It’s a poetic idea that can be traced all the way back to Fritz Lang — the city as a paranoid web of interlocking units whose overall coherence exists only in a single mind, that of an all-seeing, all-knowing Dr. Mabuse, or his equivalent. (In some of the films of Jacques Rivette, which Sleepwalk more closely resembles, this coherence becomes only an idea of an idea — a collective dream of a master plan, dreamt by two or more individuals.) In Sleepwalk this implied coherence seems to exist only in the ancient manuscript, not in the mind of any character, yet the beautiful, remote shots of the skyline at night somehow make it mysteriously legible, in form if not in content.

3. After Jimmy is accidentally kidnapped by a car thief (Richard Boes) who makes off with Nikki’s car, he is carried in a suitcase to the kidnapper’s dingy room, where, bound and gagged, he is treated to the following monologue from his captor: “I don’t come from this place. I’m from a small town. Factory town. Kind of a nice factory town. Every summer we had baseball games. My old man would take me, if he wasn’t too drunk. The guys from the asbestos plant played the guys from the steel foundry. The guys from the steel foundry always won. My old man took me to see two movies when I was a kid–The Wizard of Oz and Moby Dick.” Pause. “What am I gonna do with you?” Like Jack’s empty bedroom, this slice of nostalgia (written by coscreenwriter Lorenzo Mans) comes out of left field, yet lodges itself inextricably in the heart of the film, sending out pulsing waves in all directions. The calm, mute receptivity of Jimmy to this outburst makes it a good deal funnier.

4. The film’s centerpiece is a nocturnal elevator ride Nikki takes from the copy shop to the ground floor — seven flights down, with the elevator stopping at every floor. Like Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole or the poet’s glimpses of various rooms through keyholes in Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet, this bracketing of diverse spectacles within a single trajectory encapsulates the film’s method throughout. On the sixth floor, a little boy is packing women’s red shoes, similar to Isabelle’s, into boxes. On the fifth, there is only darkness and the sound of footsteps. On the fourth is a sinister-looking man who wants to take the elevator up. On the third are Dr. Gou and Barrington, in a room strewn with hundreds of almonds that we’ve glimpsed before. (“Ah, it’s you!” declares Gou. “We’re in the same office building!”) On the second, a bird caws and beats its wings desperately against the elevator door’s window. And on the first, Nikki walks out to the street, apparently free, where she’s confronted again by Barrington with his missing fingers.

Critic P. Adams Sitney has grouped together a number of experimental films — including Un chien andalou, The Blood of a Poet, Meshes of the Afternoon, Fireworks, and Flesh of Morning, among many others — under the general category of the “trance film.” Properly speaking, according to existing laws that dictate what does and doesn’t belong in the experimental canon, Sleepwalk doesn’t begin to qualify: it was shot in 35-millimeter, and in form it appears to be — indeed, it deceptively offers itself as — a straightforward narrative. Unfortunately, if you try to make sense of Sleepwalk as a mainstream narrative film, you won’t have much luck either.

So where does the film belong? Is it a trance film without the allegorical, intellectual, or budgetary trappings usually associated with the genre? Or a narrative film without the thematic and stylistic coherence usually associated with narrative? A poetic fantasy, yet independent of much of what this culture regards as poetry and fantasy, it belongs on its own dreamy wavelength, offering its chiseled beauty, delicate textures, and disquieting wit to any spectator game enough to climb inside.