This article was commissioned by and published in the Canadian online magazine Synoptique in its 7th issue, devoted to Susan Sontag and edited by Colin Burnett (dated 14 February 2005, about six weeks after her death), and is also reprinted in my Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

Goodbye Susan, Goodbye: Sontag and Movies

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

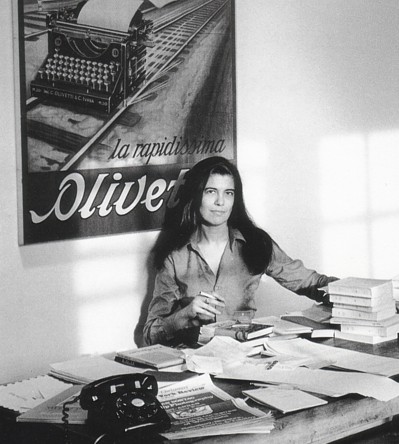

I don’t think that Susan Sontag was a great film critic; to hear her tell it, she wasn’t really a critic at all. But it’s still hard to overestimate her importance as an American writer in relation to movies. The last of the great New York intellectuals associated with Partisan Review, she was the only one in that crowd who understood and appreciated film in a wholly cosmopolitan manner, as a part of art and culture and thought —- something that couldn’t be said of Hannah Arendt, Saul Bellow, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Mary McCarthy, Philip Rahv, Harold Rosenberg, Edmund Wilson, or any of the editors at the New York Review of Books. Even if one considers the most sophisticated members or fellow travelers of that group who functioned as film critics —- James Agee, Manny Farber, Pauline Kael, Dwight Macdonald, Delmore Schwartz, Parker Tyler, Robert Warshow —- none of them could claim quite the same global, cultural, and historical reach that Sontag had. Farber possibly came closest; and also undoubtedly, like most of the others, he came much closer than her to grasping particular surfaces as well as moments in film. Her turf was closer to being philosophical, though the paradox for acolytes like myself is that we learned things from her that made her into a sort of intellectual journalist —- precisely what she didn’t want to be once she established her name, aside from a few exceptional forays such as “Trip to Hanoi”. To a certain extent, the same was true of Godard, who was only a couple of years older, and who in the 60s also became a kind of cultural journalist in spite of himself, in his films and his interviews. “What I don’t like [in Against Interpretation],” Sontag wrote in 1996, “are those passages in which my pedagogic impulse got in the way of my prose. Those lists, those recommendations! I suppose they are useful, but they annoy me now.”

No less annoyed, it seems, were some of her editors: in the first chapter of my book Movie Wars (2000), I went into detail about the censorship of her essay “A Century of Cinema” the same year, when it first appeared in English, in the New York Times Magazine, under a different title (“The Decay of Cinema”) — a systematic deletion of names of filmmakers and film titles that weren’t already thought to be familiar to Times readers. Yet even though this may be my least favorite of Sontag’s essays about film (second only to “Novel Into Film: Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz,” the only other one collected in Where the Stress Falls — which for me founders in part on the common misperception that Greed is simply a paragraph-by-paragraph adaptation of McTeague), its saving grace for me is precisely its useful lists and recommendations, all intended as exceptions to her apocalyptic argument about cinema when I’d rather regard them as refutations. After all, it was earlier references of this kind in her essays that had first introduced me to writers like Francis Ponge and Carlo Emilio Gadda. And I suppose that her gloom and doom about the death of cinephilia, so deeply inflected and in many ways determined by her refusal of TV and video, was ultimately defensible in those terms given that her love of movies was chiefly visceral. It only became “film” as opposed to movies when she wound up writing about the subject, which she liked to do less and less.

***

When I suggested to a friend and fellow English major at Bard College that our literary speakers club invite Sontag to give a talk (it was late fall or early winter, 1964), I’d read her two theater chronicles and “Notes on `Camp’” in Partisan Review and her essay on Vivre sa vie in Moviegoer. I’d also seen her once on a literary panel at Columbia with Ralph Ellison and Stanley Edgar Hyman. What impressed me most in her writing was the polemics of the theater chronicles, which included discussions of Dr. Strangelove, The Great Dictator, and Point of Order (that is, her performance as a critic —- which I suspect is the very reason why these were the only pieces in Against Interpretation that she said she disliked when she wrote “Thirty Years Afterward…” in 1996, which also recorded her misgivings about her lists and recommendations), the forms of the other two pieces (with their numbered sections), and the fact that all four articles treated film as part of art and thought without any sort of self-consciousness or special pleading —- an approach that seemed virtually unprecedented at the time. It wasn’t because I agreed with much of what she was writing about particular films; it was because it seemed like she was reinventing some of the rules by which such films could be written about.

When the invitation to Susan went out, “Notes on `Camp’” had either just provoked an article in the New York Times Magazine or was about to, but neither Time’s December 11 story about the Camp piece (which is reportedly what catapulted her into the mainstream) nor the essay “Against Interpretation” in the December Evergreen Review had appeared. When I finally met Susan on campus, where she had driven up with a friend, she was livid about just having encountered a smart-ass student who’d asked her, after recognizing her name, whether she was “real or intentional Camp”. As she said later, “I didn’t know whether to burst into tears or kick him in the balls.”

It was a memorable evening. She read and discussed portions of her just-completed essay “On Style,” and I was especially gratified by some of her films references —- Josef von Sternberg, The Lady from Shanghai, Leni Riefenstahl —- which in effect ratified recent inclusions of mine in the Friday night campus film series that I’d been criticized for showing. But what really won me over to her was, after speaking about my desire to write an article for Moviegoer about Sunrise, my favorite film at the time, her account of how the film had made her weep —- at the same Columbia University screening I’d attended a couple of years earlier.

Later, with a group of other instant acolytes, we went off to a local bar, where some of the passions she expressed were for Godard’s Contempt (which she’d already seen four or five times on 42nd Street), the literary critic Jean Starobinski, and whatever rock song was playing on the jukebox as she sashayed over to the cigarette machine. Above all, it was the singular mix of such enthusiasms that made her so sexy and vibrant, combined with an almost Latin fusion of mind and body that felt liberating in the same way that living in Paris did, when I eventually moved there towards the end of the 60s.

It’s hard to convey now how threatening she used to be to English department types (among others) during that period, when her influence was first beginning to take hold. I recall Stanley Edgar Hyman, on a visit to Bard, once admitting to me how friendly he found her when he met her —- which surprised him given how much he associated her with “the homosexual mafia”. When I attended graduate school at Stony Brook, Long Island after graduating from Bard, simply mentioning her name was often all it took to provoke a violent response from some of my colleagues, who often lunged at her sexuality, as if that immediately explained everything. (“I wouldn’t trust her around my daughter,” the novelist Jim Harrison declared to me, with a touch of bravado, when I once suggested inviting her to campus to give a talk.) But it’s also important to recall that Godard was hated by many of the same people in that period and for similar reasons, so the homophobia in Susan’s case was something of a smokescreen, a diversionary tactic. Despite her bohemian taste for dressing in black, she wasn’t really a beatnik, yet the sense of fun as well as freedom that she projected in relation to the arts often made her seem like a kindred spirit. Even her slang was that of a hipster.

***

Another thing that enhanced this quality over the years to come was her uncategorical resistance to academic film study as it slowly began to rear its head in the 70s. The only time I recall her ever expressing this resistance overtly was the last occasion when I spent an evening with her, in Chicago in the early 90s. She’d been invited by Miriam Hansen to speak at the University of Chicago’s inauguration of its Film Studies Center, a fairly posh event, and her talk, entirely improvised, was essentially an extremely tactful and graceful repudiation of academic film study, delivered in a way calculated to offend no one. This basically took the form of recalling her early encounter with Kenneth Anger films when she attended the University of Chicago as an undergraduate, and her subsequent regular attendance in New York at the Theodore Huff Film Society, a mainly all-male congregation of hardcore film buffs (in its latter years presided over by William K. Everson), and some of its cultish habits and fetishistic rituals. Implicit in all this was a declaration of allegiance for the very sort of maniacal, unreasoning cinephilia that most Anglo-American academic film study is dedicated to undermining or eliminating, though she never said this directly. (The fact that French academic film study is generally more friendly to cinephilia is worth noting, though the reverse isn’t always true, and Susan’s regular visits to the Paris Cinémathèque didn’t necessarily make her any closer to French film academics. But she didn’t ignore film academics the way mainstream critics usually do, either; I once learned from David Bordwell that his book on Dreyer prompted her to send him a fan letter.)

Afterwards, at a small gathering held in Miriam’s apartment, we spoke for a bit about Orson Welles. This is Orson Welles, the book by Welles and Peter Bogdanovich that I’d recently edited, had just appeared, and Susan asked me to go through the index of Miriam’s copy and read aloud to her all the references to Danton’s Death —- Welles had mounted a stage production of the George Büchner play in the 30s —- which she was interested in directing herself. Later, when I drove her back to the Quadrangle Club, where she was staying, I recall her mentioning that her best friend when she’d attended the University of Chicago as a teenager was Mike Nichols. This put an interesting spin on a comment she’d once made to me about two decades earlier, at the Cannes Film Festival, when I was enthusing about Gravity’s Rainbow and saying what a great movie I thought it could make. “Let’s just hope that Mike Nichols doesn’t get his hands on it,” she said, obviously thinking of Catch-22.

***

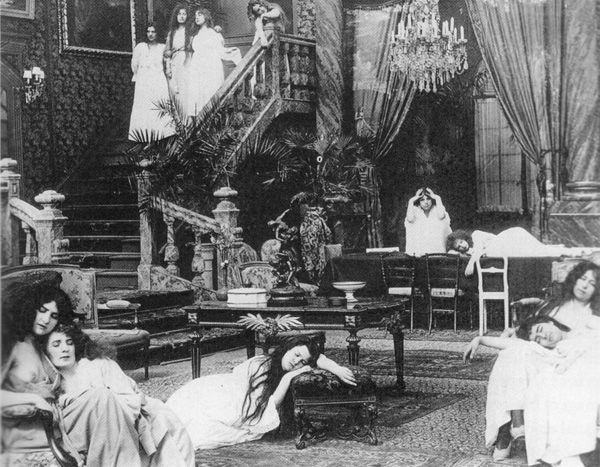

Most of my other encounters with Susan over the years were film-related. A characteristic one: watching Louis Feuillade’s seven-hour silent serial Tih Minh at the Museum of Modern Art in the late 60s, then joining her and Annette Michelson at a nearby coffee shop, where I invited her to update her Bresson essay to include discussions of Au hazard Balthazar and Mouchette for an anthology I was editing (never published). She explained that she was more interested in what Bresson’s earlier films did, which is what she’d already written about, adding that she wasn’t too keen to write more about film anyway. And if she were, I asked, who would she want to write about? Vertov, she said, without a moment’s hesitation.

I also recall a private screening in Paris of her third film, a documentary about Israel called Promised Lands (1974); Bresson himself attended, and she greeted him, effusively, as “Cher maître”. I still haven’t caught up with her fourth and last film, Unguided Tour (1983), but then again it’s hard to think of any well-known filmmaker whose films are harder to see than hers —- which makes me more cautious about dismissing them than some of my fellow reviewers. How can we be sure? The one time I saw Duet for Cannibals (1969), it meant almost as little to me as her first novel, The Benefactor (1963) —- or her last, for that matter, which I couldn’t finish. But when I saw Brother Carl (1971) at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, I liked it enough to defend it in the Village Voice, and still found it interesting, albeit problematic, when I got to see it again at a New York screening with Susan in attendance in the early 80s.

It was also at the Cannes festival in the early 70s that I told Susan about the screenplay I’d been commissioned to write adapting J.G. Ballard’s The Crystal World for a fledgling producer, Edith Cottrell, who owned the rights and was hoping to find someone interested in directing it. “I’m interested,” Susan declared, and back in Paris I wound up spending an afternoon with her in her garage flat behind Nicole Stéphane’s house, engaged in what I suppose could be called a script conference. She wasn’t too enthused about what I’d written so far, but insofar as I’d been interested in the script mainly as a way of paying my rent —- and had so little confidence in it being filmed that I wasn’t even making a carbon copy — I could hardly blame her. Still, the prospect of working for Susan made it much more interesting, so I eagerly went off to follow her suggestions about making the whole thing “sexier,” not realizing at the time that her own interest in the project most likely evaporated on the spot. She was rather awkward in explaining this when I finally managed to reach her again on the phone, and by the time she’d arranged to return a copy of Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men that I’d lent her, it finally dawned on me that we wouldn’t be having a second script conference.

I never held it against her. But I did start to harbor a grudge for another reason in 1980, when we were both back in New York. At a New York Film Festival party, she asked me what I’d been working on, after speaking favorably about my 1978 collection Rivette: Texts & Interviews, and when I told her I’d just written an experimental autobiography called Moving Places: A Life at the Movies that Harper & Row was about to publish, she brought me up short by saying, “You’re too young to write an autobiography!” Her snap judgment was non-negotiable; the implication was that at 37, I’d been wasting the past couple of years of my life doing such a stupid thing, and my having previously regarded her as the book’s ideal reader could only have been a profound misconception.

I can still find some traces of that grudge in the mixed (though respectful) review of Under the Sign of Saturn that I published in Soho News a month later — although I must say that I still agree with most of its conclusions. (It was in that book, after all, where she momentarily seemed to come dangerously close to replacing Godard with Woody Allen and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg.) After praising her first two collections, I added, “Speaking as someone who used the parenthetical examples of those essays rather like the way an earlier generation used Eliot’s footnotes to The Waste Land —- as a central tool in my liberal arts education —- I am disappointed at not being able to appropriate Sontag’s recent, more inner-directed essays in quite the same fashion. As an old college friend observed recently, `She doesn’t belong to us anymore.’”

Some time later, when we met again at the Brother Carl screening, she graciously deferred to me during the discussion, asking me to explain to the audience who her actor Laurent Terzieff was, and afterwards she said to me something like, “I have the impression that you’re sore at me because I didn’t want to read your book.” Since she professed never to read the reviews of her own books, I wasn’t quite sure how she’d arrived at this correct assumption, but I stammered out a shameful disclaimer on the spot. And the next day made the even bigger mistake of sending her an inscribed copy of Moving Places, which I’m fairly sure she never read. Yet once my book was eventually praised by Godard, her supreme idol, in one of his interviews, I could safely assure myself that her validation no longer mattered, and that I could revere her just as much without it.

Over the years, at various times, we had many friends in common —- Stephen Koch, Annette Michelson, Paul Thek, Elliott Stein, Marilyn Goldin, Gary Indiana, Noël Burch, Edgardo Cozarinsky, Béla Tarr —- so it was often possible to feel in touch or at least au courant with Susan even when I didn’t see her for long stretches. I was delighted to hear from Edgardo about what a breakthrough The Volcano Lover had represented for her —- not simply because it put her in touch with a wider public, but more crucially because it allowed her to write fiction and essays at the same time. And what remained an inspiration about her up to the very end (and beyond) was the sheer will to live that delayed the death sentence handed to her by her cancer for longer than most people expected, including her doctors, and the courage to fight whatever obstacles stood in her way. In short, what I think Susan taught me and countless others by her example was her way of being in the world. What she had to say about film was ultimately an extension of that.